Hunting for marriage: Inside Japan’s matchmaking crusade

To Koki Goto’s relief, the clouds part by early afternoon and the Hamarikyu Gardens in central Tokyo are doused in sunshine — perfect weather for couples to take idyllic strolls around the compound’s immaculately maintained hedges, ponds and lawns.

Twelve nervous men and women have gathered here on this Sunday in late April for a matchmaking event. But before any romantic sparks can fly, they’ll need to get to know one another.

“Thanks for attending the meetup today. I’d like to begin by asking everyone to briefly introduce themselves,” Goto says from the far end of a tatami-floored room in a traditional tea house sitting in one corner of the gardens. Goto heads an organization called J-konkatu, which is dedicated to introducing potential couples in the hope that they’ll eventually want to tie the knot. The group holds events like this at various points throughout the year.

Sitting attentively on their cushions, participants take their turn: “I enjoy going on drives and eating good food,” says a clean-shaven, 37-year-old self-employed man, playing it safe. “I’ve recently gotten into watching pro-wrestling matches,” says a 32-year-old woman working for a nonprofit, her rather unexpected hobby drawing good-natured laughs. (Most of the participants ask to remain anonymous for this story.)

“It’s more about practicing how to socialize with the opposite sex,” Goto says as the party splits into male-female pairs, with each taking four-minute turns chatting across tables.

“Generally speaking, the Japanese aren’t very good at developing romantic relationships,” he adds. “So I don’t really expect couples to be born right here at this event. Instead, I want them to be more confident talking to other people.”

Matchmaking is taking on increasing importance in an aging, shrinking nation in which the number of marriages have been dwindling for decades.

In Tokyo’s neighboring Yamanashi Prefecture, for example, residents can search for soulmates via online avatars in the metaverse. In Aichi Prefecture, organizers are preparing for one of the largest matchmaking parties ever to take place in the nation, inviting 400 men and women for a massive meet-and-greet in October. Meanwhile, the konkatsu (matchmaking) market is overflowing with apps catering to a growing population of singles.

Earlier this year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida declared that his government will take “unprecedented” measures to tackle Japan’s falling birthrate, and stressed that it was a case of “now or never” to reverse the nation’s demographic crisis, which is already weighing heavily on social security costs.

In a country where children born out of wedlock account for only 2% of all births, the number of married couples has a strong correlation with the number of newborns. Finding a life partner, then — whether it be through apps, meet-and-greets or traditional arranged marriages — could hold the key to the future of Japan’s economy.

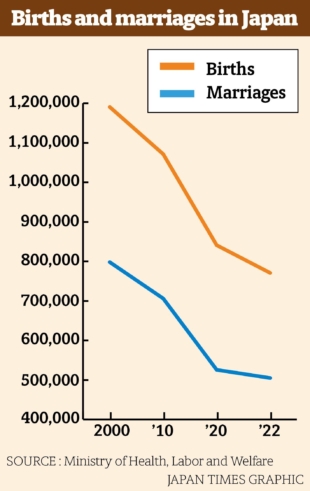

Falling numbers

According to the health ministry, Japan saw 504,878 marriages in 2022. That’s compared with 706,000 in 2010 and 798,000 in 2000, which translates to a 37% drop in a little over two decades. Meanwhile, the number of newborns fell to 770,747 in 2022, the lowest since the government began keeping records in 1899. Total deaths rose by around 129,000 to 1.57 million that same year, while Japan’s population has steadily fallen from 2008’s 128.1 million to 124.5 million in May.

Highlighting the scale of the problem are the various surveys taken on Japanese attitudes toward relationships and marriage. According to the White Paper on Gender Equality 2022 published by the Cabinet Office, 65.8% of men and 51.8% of women in their 20s said that they had “no spouse or partner” in a survey taken in 2021. Among those in their 30s, 35.5% of men and 27.0% of women said they were single.

Meanwhile, a nationwide survey conducted by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in 2021 and released last year saw a record 17.3% of men and 14.6% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 say they had no intention of getting married during their lifetime.

And that has played a role in a troubling statistic: Japan’s total fertility rate in 2022 was 1.26, well below the replacement rate of 2.1, the average number of children per woman necessary to prevent population decline.

Various factors can be attributed to the phenomenon. For one thing, women opting to have fewer children and having them later in life is a growing trend in wealthy nations — as countries get wealthier, their birthrate typically declines. A lack of affordable child care, adequate paternity leave and other support measures are also cited as reasons.

In Japan, however, a sluggish economy and growing income disparity, as well as traditional gender norms that expect men to be primary breadwinners, are considered major hurdles hindering marriage prospects.

“People just aren’t earning enough to support a family,” says Masahiro Yamada, a sociologist and professor at Chuo University.

The ballooning number of so-called nonregular workers, or those hired on a part-time or temporary basis and who typically earn less, isn’t helping either, as they now account for around 40% of all workers.

Rising prices are making matters worse. Nominal wages rose 1.9% in the last fiscal year, which ended in March, the fastest increase in 31 years according to government data. But inflation at 3.8% outpaced those pay gains, resulting in real wages falling 1.8% in fiscal 2022, the biggest drop in eight years.

Lower incomes are a major marriage deterrent not only for men in Japan, but also those in East Asia, Yamada says, where they are often expected to solely provide for the household.

“That means rather than moving into a new home with a partner and splitting the bills, it’s often easier and more comfortable for lower-income earners to live with their parents,” he says. Yamada calls them “parasite singles,” a term he coined referring to those living with their parents beyond their early 30s.

“That’s the case not only in Japan, but in Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong, for example,” he says. “I can’t see the trend in declining birth rates stopping anytime soon.”

‘Focus period’

Back at Hamarikyu, the 12 participants separate into two groups for a walk through the garden. Among them is 40-year-old Yuzo Oshima, properly dressed for the occasion in a blue blazer and striped shirt. A deputy manager for a Tokyo-based manufacturing company, it’s the third time he has joined Goto’s event.

In the same group is the pro-wrestling fan. Petite and wearing a black skirt, she appears to have locked her attention on Oshima, sticking by his side. Later, after the three-hour event wraps up, Oshima tells me he has exchanged contacts with her on the messaging app Line.

An eloquent speaker with a stylish, asymmetrical haircut, Oshima doesn’t come across as someone who would have difficulty getting into relationships. In fact, he ended up dating a fellow participant when he attended one of Goto’s events for the first time back in 2017. They went out for two years, and Oshima proposed to her when he thought the time was right.

“But she told me she wasn’t ready,” he says. They broke up. He then dated a co-worker, but they parted ways recently, and he found himself back on the market.

“I’ve tried dating apps as well, and they have their benefits and drawbacks,” he says. “The merits of these events Mr. Goto hosts is that you can skip the initial online exchange and go straight to meeting people in person.”

One of the services Oshima tried is a so-called kekkon sōdanjo, or a marriage counseling agency, a term that now typically refers to a service that’s a hybrid between online matchmaking and in-person marriage counselors offering advice. Among the largest around is Zexy Enmusubi Agent.

“While marriage counseling in Japan often conjures up images of chatty, middle-age women arranging one-on-one dates, our staffers are in their 20s and 30s, closer in age to our clients,” says Rieko Oka, a manager at Recruit Zexy Navi’s matchmaking business department.

After paying a ¥33,000 admission fee, members can select from three monthly plans. The standard plan, for example, allows them to go through the online profiles of registered users and request meetings with up to 20 people a month. A personal “matching coordinator” will, in the meantime, also offer clients six recommendations a month based on their background, tastes and other criteria.

“Once the so-called trial period when they meet many people is over, we move on to what we call the focus period, where clients concentrate on developing deeper relationships,” Oka explains.

“Upon request, we offer various advice along the way, such as what clothes to wear on dates. And when a client is ready to propose, the pair’s coordinators can discuss how their clients feel toward marriage.”

Double-edged sword

The world of dating apps often relies heavily on self-commodification, which can be a double-edged sword.

In 2013, Misanori Takahashi, an associate professor at the Tokyo Metropolitan University, installed his first dating app on his iPhone. He was 38, and figured it was about time he began looking for a significant other rather than going on solo fishing expeditions and ramen binges.

Being an economist, however, he soon discovered that such apps operate on what he calls the “dynamics of comparison.” Upon creating profiles, users are asked to upload photographs of themselves and enter their salary level, education, hobbies and other information that helps them stand out. Those browsing through profiles can, conversely, narrow their search depending on what they’re looking for.

Dating apps can also be dehumanizing, he continues. Since there are no personal connections between registered users, people are less hesitant to act rudely — abruptly cutting off communication, for example — or not showing up for dates.

“I’ve also had women meet me just for free meals,” he says. “And it’s not just with apps — when I attended a meet-and-greet in Ginza once, I almost got persuaded by an attendee into buying a ¥200,000 Hermes bag for her.”

Now nearing his 50s, Takahashi says he’s given up on finding a partner. “Considering my age, I’ve figured I’m better off spending my time on hobbies and things I consider important,” he says.

Virtual platform

Some organizers have realized the drawbacks of the excessive self-branding and marketization inherent in online meets, and have taken a different approach to matchmaking.

“Most of the participants in online events prioritize looks and age — turnoffs for people who aren’t as confident with themselves,” says Yurie Sasa, an official from the city of Hokuto in Yamanashi Prefecture tasked with marriage consultations.

The metaverse is increasingly becoming a part of efforts to spur marriage in Japan, with matchmaking events allowing people to meet virtually through avatar characters. | METAVERSE MATCHMAKING ASSOCIATION

As is the case with many regional municipalities in Japan, Hokuto has been suffering from depopulation and has been hosting matchmaking events as part of its efforts to stem the demographic drain.

“We decided to host an online matchmaking event in the metaverse, and have people join via avatars,” she says, referring to an immersive version of the internet. The anonymity helped those from more rural areas where gossip is rife to join without the fear of their neighbors finding out, she says.

Once a match is made on the virtual platform, the avatars go out on two one-on-one dates before exchanging contacts.

“They finally meet in person on their third date,” Sasa says. “By then, they seem to have a good idea of each other — we haven’t heard any complaints so far.”

Use of such local initiatives aimed at encouraging relationships, be it online or offline, is expected to accelerate in the coming years.

In April, the government launched the Children and Families Agency to oversee policies relating to children as part of Kishida’s effort to reverse Japan’s declining birth rate. Reports say that under a new program, “marriage support concierges” will be deployed to all 47 prefectures, and housing subsidies for newlyweds will be expanded.

Yuzo Oshima has tried a marriage counseling agency and matchmaking events in his quest for love. | ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Meanwhile, Oshima’s matchmaking crusade continues. Catching up a month after the event at Hamarikyu, the 40-year-old bachelor says he asked the pro-wrestling fan on a date.

“I felt we had common interests and we enjoyed a good conversation. I then invited her on a second date, but unfortunately I haven’t heard back,” he says. “While it has become easier to meet people, I also think communication is lacking.”

He hasn’t sworn off love just yet, though. Oshima has signed up with Goto’s J-konkatu for a one-on-one, in-person matchmaking service for those serious about getting hitched as soon as possible.

“It’s all a learning experience,” he says.

Recent Comments