Kidnapping Survivor shouts “stop scrolling!”

Each day, Kozak was uploading new videos of missing persons to her Instagram and TikTok, where she has a combined 265,000 followers. She encouraged users to circulate the missing persons’ posters in the hopes of bringing them home.

Kozak said that thanks to social media, users have the power to share these posters with millions of other people across the globe “in seconds.”

“I was one of the lucky ones, but we don’t have to leave it to luck.”— Alicia Kozak

In the comments section of Kozak’s poster videos, people are trying to ignite conversations about her posts, even sharing their favorite colors or their pets’ names. They’re doing anything they can to increase viewers and the number of shares.

“It’s about engagement. People want to help that video be seen by others,” Kozak said.

North Carolina woman has so far shared 30 missing persons’ posters on Instagram and TikTok

Stop scrolling. I need your help.”

With these six words, Alicia “Kozak” Kozakiewicz is doing everything she can to help those who are missing be found.

Kozak, a motivational speaker and internet safety expert in Raleigh, North Carolina, was 13 years old when she was lured from her Pennsylvania home and kidnapped by an online predator before he transferred her to Virginia, Kozak told Fox News Digital.

Kozak, 35, credits her “miraculous” rescue to the work of her missing person poster that at the time was seen across the U.S.

“I want to help share that miracle with others and give others the chance of that miracle,” Kozak shared.

Kozak was just 13 years old when she went missing from her Pennsylvania home before she was found with the help of her missing person poster (shown here). (The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children)

Kozak uses her online platform to share the posters of missing individuals who may not be getting as much news coverage as other cases.

“Every missing person deserves media attention,” said Kozak. “Unfortunately, sometimes that isn’t feasible and the stories that are told are likely to be limited.”

“Through the ‘Stop scrolling!’ videos, we’re able to give the missing person a greater chance of being seen and recovered,” she added.

In 2002, FBI agents stormed the property where she was held captive on Jan. 4 – four days after she was declared missing.

Her attacker, whose name she will not mention, reportedly served at least 17 years before violating the terms of his parole, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

The man is no longer in prison, Kozak said.

Since she was set free, Kozak uses her experience to try and help save the lives of others.

In May, which was Missing and Unidentified Persons Awareness Month, Kozak — with the help of her boyfriend Eric Lind — used her platform to launch a “Missing Persons Challenge.”

Kozak has spoken with family members of those she’s highlighted over the past month, and some have reached out to her asking to make a video of their loved one who is missing.

“One of the most important things is hope — and what I really wish is that these posters provide that hope and that support to that family who has maybe been working to get that story out there, and they feel helpless,” said Kozak.

“It is one of the most helpless situations to have somebody be missing,” she continued.

“You don’t know where to go, you don’t know where to turn and often the media doesn’t listen.”

When it comes to missing persons, people may make assumptions as to why a person is missing and end up believing that “they are somehow less worthy of being found,” Kozak said.

“Every missing person deserves to be found,” she added.

“It doesn’t matter what their background is [or] what they’ve been struggling with. If anything, it’s more of a reason to be concerned.”

Kozak recently shared the poster of a missing person who was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, Kevin Eby — and interviewed his wife and son on her YouTube channel.

While Kozak may never have met those who were missing, she does feel impacted by their stories after communicating with their families, she said.

Kozak said that while not all stories have a happy ending, families just want an answer, or at least hope.

“What kept me going was that I knew my family loved me and I knew they were looking for me,” Kozak shared.

She went on, “I knew they were going to do anything and everything to find me and I held onto that hope and I held onto that love — and that’s what got me through it.”

“Somebody somewhere was the last person to see the missing person. Somebody somewhere has the answers, and we can bring those answers to light.”— Alicia Kozak

Hope prevailed as Kozak was brought out of her nightmare and reunited with her family.

“It wasn’t until my dad hugged me that I knew I was saved and nothing and no one would hurt me again,” Kozak stated.

Kozak remembers her dad saying, “If we could duplicate that hug all over the world there would be no more wars.”

Kozak hugged her father after she was reunited with her family — and she remembers her day saying, “If we could duplicate that hug all over the world there would be no more wars.” Here, Kozak is photographed with her parents, Mary and Charles Kozakiewicz, after FBI agents rescued her from her captor. (Alicia Kozak)

Kozak said, “That hug was so powerful. It was safety, it was security, it was a miracle.”

Kozak started sharing her when she was just 14 years old – one year after being rescued. She said it’s been her purpose as she was “given a second chance at life.”

“If my poster was not out there I do not believe that I would be here today,” she added.

Kozak has been an advocate for missing persons since she was 14 years old. She speaks across the country and works alongside organizations such as the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. (Alicia Kozak)

Kozak has testified before Congress in hopes of passing “Alicia’s Law,” which provides “a dedicated steady stream of state-specific funding to the Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Task Forces,” according to her website.

Alicia’s Law has been passed in at least 11 states.

She also founded the “The Alicia Project” as a way to promote “internet and child safety awareness, advocate for missing and recovered persons and battles against child sexual exploitation and human trafficking.”

Kozak has worked alongside the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), but she credits her boyfriend, Lind, for his help on the “Missing Persons Challenge.”

“He has helped me with this more than I could have ever asked,” Kozak said.

“I find it beautiful how the people commenting connect over shared hope. Hope is powerful when magnified.”— Alicia Kozak

Lind has been the editor on Kozak’s TikTok videos and Instagram Reels – making them extra engaging for audiences.

Many of their videos have been seen by hundreds of thousands of people with the goal of tracking down the missing.

“I find it beautiful how the people commenting connect over shared hope,” Kozak said. “Hope is powerful when magnified.”

Kozak believes there is a direct correlation between the amount of missing persons recovered and their very public poster. (Alicia Kozak)

Fox News Digital was unable to track down up-to-date statistics on the success rates of missing person posters being the key to tracking down missing or unidentified people, though Kozak said she feels the visual is effective in many ways.

“I do believe that there has been a direct correlation between these videos and several of these missing people returned home,” Kozak commented.

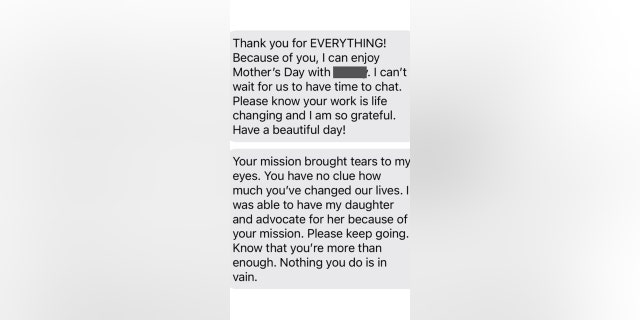

“I do believe that there has been a direct correlation between these videos and several of these missing people returned home,” Kozak commented. Here, a parent thanks Kozak in a private message for bringing attention to their missing loved one’s case. (Alicia Kozak)

Kozak’s advice is for everyone to have a decent photo of a loved one handy.

“Please make sure that you have a clear current photo and that’s not to say something bad is going to happen to you family member or that they will go missing, but it’s really good to be prepared so you can put the best information out there,” Kozak explained.

It is estimated 460,000 children are reported missing each year.— National Crime Information Center

Missing person posters have been circulating since the National Child Safety Council initiated the “Missing Children Milk Carton Program” in December 1984.

The Library of Congress considers Etan Patz to be the “first missing child on a milk carton.”

As technology improved, posters are now more visible outside of milk cartons, police stations or storefront windows.

In 2015, the National Crime Information Center, along with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, estimated around 460,000 children are reported missing each year.

Kozak will continue to make more videos in hopes of recovering more individuals and reuniting them with their families, she said. (Alicia Kozak)

Kozak realizes she cannot help find every single child or individual who goes missing, but she’s determined to try.

“Somebody somewhere was the last person to see the missing person,” she said. “Somebody somewhere has the answers, and we can bring those answers to light.”

“I was one of the lucky ones, but we don’t have to leave it to luck. We can all take action and help.”

Recent Comments